“The ability to do a running spiral is priceless” – a chat with Dave Alred, kicking guru

I chatted to kicking and performance coach Dave Alred about place kicking, his influences and the lost art of the spiral kick. Later I would try not to embarrass myself in a training session with the man while an Irish rugby great looked on. We’ll get to that. All in good time. So settle in.

Dave Alred was at Carton House last week to give an hour’s talk at a BT/Setanta Sports event for their clients and customers, followed by a Q&A session. Now living in Bristol but born in London, he currently coaches Irish kickers Jonathan Sexton and Paddy Jackson along with Cardiff’s Rhys Patchell and Bath’s George Ford. But it’s fair to say he’s probably best known for being the kicking mentor of the now-retired kicking great Jonny Wilkinson.

“Can you get me a sandwich?” asked Alred, followed by a nod from one of the Setanta folks. It was past 1pm and there was a kicking session to come. He hadn’t eaten since breakfast, I supposed. “Didn’t have breakfast” said Alred, who looked tired.

We sat down on a comfortable sofa in the hotel reception of Carton House and started to talk.

Centre of Gravity, and The Influence of Other Sports

Alred has taken inspiration from other sports in developing his theories, for both rugby and golf. He mentions Aussie Rules, in terms of kicking technique, and Judo: “a really good education for me in terms of understanding what the centre of gravity is”. American hardball, too.

“Baseball, obviously that relates to the centre of gravity, where the impact position is in relation to your centre of gravity and how it relates to both golfi and for goalkicking – it’s exactly the same thing”.

Alred motioned towards the low table in front of us: “For example, if I hit a ball and there’s the impact position where the table is… [points towards table, leans forward] my body needs to be over it to be powerful, not sitting back here [leans back in the sofa]”.

Alred is very big on the concept of the “pillar”, the main (crotch to neck) body mass, and would stress this throughout the afternoon to come. “One of the crucial things in golf, in rugby goalkicking and indeed penalty taking in soccer is that the pillar should do the work. In other words, if you define the pillar from the crutchii to the top of your head as a tube, that should always shift to the target and it should be the prime mover. If that becomes the prime mover then the leg becomes an accelerator.

“If you look at baseball, they twist first and try and delay the arms. You look at fast bowling, it’s the same thing – you let your hips thrust through, then your pillar comes afterwards and when the pillar’s in the right position the arm comes through”.

He calls it a “kinetic chain” which works from the bigger muscle group first and on through the smaller ones. “Golf is a prime example. You get your quads moving first, that’s the bigger muscle group, then you would twist with your pillar then your arms would come in and then your wrists would go. Having that chain, that’s the thing that actually produces speed but, as importantly, it also helps you to produce stability on the impact. And balance”.

Why Do Test Kicking Rates Drop So Fast After 35 Yards?

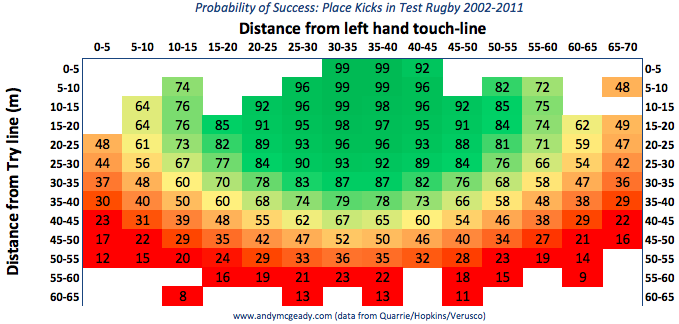

I ask about Alred’s views on why, as a group, rugby union kickers at the top level see their success rates drop ferociously fast after the 35 yard mark – is that simple physics or technique breaking down?

“It’s two things” Alred told me. “The dynamic of the ball is such that you can hit it 30 to 35 yards, hard, and it will go straight. It only deviates from wind or conditions when it slows down.”

Alred says most kickers generally possess about the same amount of kicking power, with a small number able to extend that 30-35 power range out to beyond 40 yardsiii.

“If you’ve got a kick 20 yards in front of the posts and the wind is blowing across, some people say ‘I aim for the far post’ then they end up hitting it perfectly, and it hits the post. It goes exactly where they aimed. What they don’t quite understand is that the bend will only come after about 30 yards.

“So if you then follow that argument back, really, windiv only affects the kicker after a certain distance. That’s why that sudden drop off happens.”

Jonathan Sexton 2014 – More Beef, Less Angular, Better For Kicking

Alred is currently working with Jonathan Sexton, an arrangement in place for, he says, about four years now. Are people right to question the amount of time he sometimes stands over the ball?

“It’s quite interesting. When you look from the outside, and you say – ‘well he’s taking a long time over the kick’ – there are certain things that are going through this mind. A specific routine. And it’s how long does it take to go through that routine? If you look at Wilkinson for example, one of the things we looked at was always – go back, step, and then he’ll move his feet. Because he needs to get in a position where the ball looks comfortable to his eyes”.

Alred doesn’t demand a particular run up. “It’s not a specific three back, three across; two back, three across; although people like to have that, some players – it doesn’t resonate with them”.

Just as some players work differently with run ups, the build of a player can also have a significant impact on technique.

“When I first worked with Jonny [Sexton] he was quite angular”, Alred told me, “and it’s important when people are angular that they build up a little bit of momentum getting into the ball. Whereas Wilkinson is not angular, he’s quite short and squat. So he can deliver power more readily.

“With the lever principle, if you’re not stable and secure then the lever loses control. So it’s always that payoff. So with [Sexton] it was a big thing about creating momentum, and he’s coming to the ball in the same way over and over and over again. That was really, really important. And he’s actually got stronger in the time that I’ve known him, he’s got stronger and he’s got bigger and heavier”.

That extra size and weight has been very good for Sexton’s kicking, said Alred. “It is lean body mass, he hasn’t put on weight for the sake of it. He’s just got bigger. And stronger. So he’s in a much better position in terms of being stable, and if you’re stable then you can deliver a lot more power”.

Why The Spiral Kick Is Becoming A Lost Art

I’d wanted to ask Alred about the spiral kick, something that has faded out of the game a little. An underused weapon, in my opinion, and remarkably so given the importance of territory in rugby. Alred agreed that it had gone out of fashion, but when I suggested this seemed to be due to an emphasis on Safety First above all else he quickly interrupted me. “I don’t think it’s for safety, I think you’re being kind there. It’s actually because it’s easier to do, and the spiral takes more time [to learn]. But if you want to be different, you work on the spiral. And Jonny [Sexton] and I are both committed to continuing to work on the spiral. Some of Jonny’s spiral kicking has been absolutely outstanding”.

He does the same work on the spiral with George Ford, he told me, and Paddy Jackson.

“The curve is completely different” said Alred, referring to that of the spiral as compared to the end-over-end style so often favoured in today’s game. “If you’re kicking for position, the spiral goes much quicker through the air; it’s much easier to penetrate that gap between 15 and the winger. Whereas if you kick a drop punt it wobbles up, and then it goes, and then it stalls, and it allows 15 to come around and take it on the run. And then 15 is running towards you with the ball in his hand and he can see everything and he pings it back down. If you drill it in the hole and 15 has to turn and go and get it, it’s an entirely different game. But, it takes work. And some players, particularly the backs, would want to look at other parts of their game”.

“The players don’t want to stay behind and learn it – if I’m in the team and I don’t have to kick, I won’t kick.”

All sense of tiredness that had been in his eyes earlier was now gone, replaced by a spark as he moved on to discuss the value he saw in having kicking options on the field.

“If you want to look at one of the reasons why Toulon were so good, it was in part to Wilkinson, but the real reason was the Wilkinson and Matt Giteau combination. They had kicking options all over the place, and it’s the kicking options that I think a lot of teams just miss out on. Because the players don’t want to stay behind and learn it – if I’m in the team and I don’t have to kick, I won’t kick”.

“The issue is that in the modern game, when the 10 shapes to kick there are at least three full backs, sometimes four full backs, when the back row drops off the lineout or whatever. If 13 kicks – so the ball’s gone 10 to 13 – there’s an entirely different shape to the defence. The winger has to come up; if he doesn’t you’re going to take an easy 30 yards. If he does come up and 15 hasn’t got across, the ability to do a running spiral is priceless. But the health warning is you’ve got to work at it. It’s got to be little and often, every day. Ten minutes, every day. And players don’t want to do it”.

One hears whispers about players who’ve place kicked in the past, whether for school or club, not wanting to bother with those extra minutes every day when they join the professional ranks. It would be a shame were rugby to take another step towards the NFL where so many players train for one specific jobv, and that job only.

Continuous Learning

Despite his years of coaching Alred doesn’t claim to know everything about kicking. He says he’s still learning. In the Q&A earlier he’d said that in the final weeks of Wilkinson’s spell at Toulon there was something they’d done for the first time ever in the week before the final. And now when working with Sexton, Jackson, Patchell and Ford there are things Alred says he is doing that he never did with Wilkinson.

“There are always challenges when working with different players and different mindsets. Golf has helped me massively in looking at things slightly differently”, Alred had told his audience. But he is firm when discussing work ethic. “I can’t stand people who don’t work”, Alred told me. “If people aren’t prepared to work then… I’m out. Now, if a golfer wants to work with me I put him on trial for two days. If I don’t feel he’s going to work hard enough I’ll just say ‘not for me’.”

Three plates of sandwiches arrived – ham, chicken salad, egg – and the recorder was switched off. Time to eat. After all, Alred had a session to take on the Carton House pitches where he would bring four young kickers through their paces, as well as a very slightly less young journalist.

Kicking School

The day’s pupils for Alred’s kicking clinic were Lansdowne J1 player Gearoid McDonald, schoolboy players Ben Mahon (CBC Monkstown) and Ben Kealy (St. Gerard’s) along with Old Belvedere kicker Josh Glynn who had kicked 14 points for the 1st XV against St. Mary’s in the Leinster Senior League Cup two weekends beforehand.

Having played many years of both rugby and soccer, your author is not uncoordinated. But the ravages of time, ligament injuries to both ankles and, frankly, the lack of anything approaching genuine talent meant that he was very much the remedial student in Alred’s class on that sunny Thursday afternoon. And, unbeknownst to the journalist when he’d packed his boots, former Munster, Ireland and Lions kicker Tony Wardvi would be watching. No pressure.

It would be a 90 minute session, ranging from drop punts to kicking on the run to drop kicksvii to place kicks and, lastly, spirals. Mostly these kicks were to be done in combinations, sometimes with the true goal of the exercise hidden until after it had been completed.

Sometimes kicking in pairs, other times game-based in front of the posts. Always with a simple, specific goal in mind. And Alred constantly moving from kicker to kicker; always alert, always watching.

Ben Kealy and Gearoid McDonald look on as Dave Alred watches Josh Glynn take a place kick. Photo Credit: ©INPHO/Morgan Treacy

The spiral kick got its own game, appropriately enough given the feeling with which he had spoken of that beautiful, arcing kicking style in our chat earlier. The game? To hit a good spiral from the 22 under the crossbar and past three defenders on the goal line.

The point of the game, he told the group afterwards, wasn’t to hit a low spiral but rather to hit an aggressive one. An aggressive spiral, said Alred, even if slightly mis-hit is still a wobbly, awkward kick to field.

Throughout the session Alred had offered simple things to work on for each of the students. One of the class had been told to generate more momentum in his run up, for example. His kicking had been all leg, no body: “If you keep kicking like that for the next 5 years, you’ll have trouble”, the kicking coach had told him. Alred’s key advice to another? To change the starting point of his runup slightly in order to approach the ball from a straighter angle; this would force his quad and laces through the ball, generating more power.

Ben Kealy helps Dave Alred demonstrate the varying strengths of a kicker’s muscles. Photo Credit: ©INPHO/Morgan Treacy

Why the quad and laces? Our adductor muscles are not as strong as our quads, explained Alred. He demonstrated this by having each of us push with one foot against the back of another person’s ankle, first with the side of the foot, then the laces.

At 4pm the mid-September sun, strong when the session had begun, was getting a little lower in the sky. Alred congratulated the group on their work, handshakes were exchanged and notes were compared.

“The key thing is, guys, when you get home write it all down”, Alred said as the group left the pitch. Hopefully they did. After all, this is the man who Jonny Wilkinson told Rugby World “changed the course of my career”.

It’s not often such apprentices get to have a session with the master.

Sponsor’s Promoviii: BT Sport will broadcast 35 live games from the European Champions Cup this season as part of the Setanta Sports Pack. Find out more at setanta.com.

Great article and insight from the man himself. It’s shocking to think there are pros who don’t want to put in the extra time, but it certainly points toward some of the average kicking displays we see these days! I just stumbled upon your blog today, but am looking forward to reading future (and older!) posts.